PUBLIC ART

BY MIGUEL PINHO

Invited authors: Miguel Carneiro and Pelucas Martin

“PUBLIC ART is a broad term which refers to artworks in any MEDIA created for and sited either temporarily or permanently in public places. Public places are generally associated with external spaces; however, artworks can be situated outside in private spaces, such as shopping malls and private housing developments, or inside in public spaces, such as publicly funded ART MUSEUMS and GALLERIES or hospitals and libraries. Consequently a definition of what constitutes public space is problematic”.1

In 2001, David Hickey2 brought together the work of twenty nine artists at SITE (Santa Fe International Biennial) in an impressive installation created by Graft Derin. Several kinds of works were presented in that installation, which significantly turned the museum into a large “Architectural Frame”. This event at SITE proved that the installation of an exhibit may adopt different strategies and configurations and that, more often than not, it is the artwork’s spatial configuration and location itself that will create a new space. In this case, the result is an impressive “Architectural Frame”, with a non-traditional configuration, where the placement of the works reinforces the innovative spatial character of the museum.

Like the artists in the seventies, who felt the need to create their own spaces to experiment with new languages and to answer the excessive “institutionalization” of conven- tional spaces such as museums and galleries, public art also tried to find an answer for the traditional classical monumentality. It is important to clarify what public art means; the defi- nition is controversial and not easy to establish with accuracy, implying different perspectives. Although easily identifiable, Malcom Miles’s description – “the term ‘public art’ generally describes works commissioned for sites of open public access” (in “Art Space and City: Art and Urban Futures”) – is still not enough to offer a coherent definition. In my opinion, Harriet Senie3 offers a more significant answer to contemporaneous impulses when she tries to define public art as a consequence of having audience as a starting point for the creation of the artwork, thus making it respond to the viewer’s perception of that very same work.

(...)

The artworks here on display, mainly chosen because their supports are several plans of building that have become derelict, belong to two authors from different fields who show strong similarities in the work they develop. They are not trying to be “main stream” nor are they exactly “against the current”. They embrace their individuality through great phantasy and imagination. They are simply artworks.

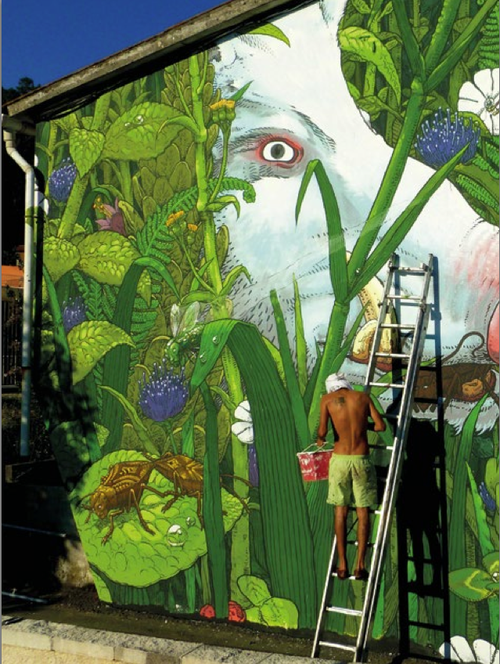

Miguel Carneiro’s intervention target “Cospe Aqui” [“Spit Here”] is well known by those of walk around Cedofeita14. Although dating back some years ago, it is still very up-to-date. Being somewhat hostile, the author states that “Who was born and has lived in Porto has an instinct to slalom between the many obstacles left by men and animals along the city pavements. (...) COSPE AQUI [SPIT HERE] stencil appears in this context, as an attempt to maximize this cultural habit as an evocative provocation. Although at first it randomly competed with other marks in the pavements, the stencil soon started to direct itself to more international targets, from political propagandas, including party headquarters and multinationals, to the most exclusive art gallery entrances, everything could become a target for the excess of saliva that we daily gather in the mouth”. The juxtaposition of the stencil with signs of political nature, near art galleries, clearly shows its interventionism, a critical message to the oblivion of some, through an image an undeni- able and much needed irreverence. On the contrary, Pelucas Martin is an author with a great graphic accuracy, who in his imaginary looks for references of his back- ground. Sometimes architectural details of that early period stand out (see the mural in the former Campanhã space, nowadays “Oficina Arara” [“Arara Workshop”], Campanhã Porto). The phantasy is rather evi- dent in the different artworks. Sometimes a kind of anthropomorphism appears, poking at the frontier of illustration, especially when referring to a set of characters who, outside their habitat, contradict the images commonly used in today’s precarious urban environments.

1 http://www.imma.ie/en/downloads/publicart.pdf

2 North-American Art critic. Author of The Invisible Dragon: Four Essays on Beauty and Air Guitar, Essays on Art and Democracy. Professor of Art Theory and Criticism at the University of Las Vegas.

3 Senie, Harriet, Contemporary Public Sculpture: Tradition, Transformation and Controversy, Oxford University Press, New York,1992.4 Cf. The presentation of several works by avant- garde artists, such as Calder, Picasso or Moore, just to name a few. mouth”. The juxtaposition of the stencil with signs of political nature, near art galleries, clearly shows its interventionism, a critical message to the oblivion of some, through an image an undeni- able and much needed irreverence. On the contrary, Pelucas Martin is an author with a great graphic accuracy, who in his imaginary looks for references of his back- ground. Sometimes architectural details of that early period stand out (see the mural in the former Campanhã space, nowadays “Oficina Arara” [“Arara Workshop”], Campanhã-Porto). The phantasy is rather evi- dent in the different artworks. Sometimes a kind of anthropomorphism appears, poking at the frontier of illustration, especially when referring to a set of characters who, outside their habitat, contradict the images commonly used in today’s precarious urban environments.